Process of removing contaminants from municipal wastewater

This article is about the treatment of municipal wastewater. For the treatment of any type of wastewater, see Wastewater treatment.

Sewage treatment plants (STPs) come in many different sizes and process configurations. Clockwise from top left: Aerial photo of Kuryanovo activated sludge STP in Moscow, Russia; Constructed wetlands STP near Gdansk, Poland; Waste stabilization ponds STP in the South of France; Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket STP in Bucaramanga, Colombia.

| Sewage treatment |

| Synonym |

Wastewater treatment plant (WWTP), water reclamation plant |

| Position in sanitation chain |

Treatment |

| Application level |

City, neighborhood[1] |

| Management level |

Public |

| Inputs |

Sewage, could also be just blackwater (waste), greywater[1] |

| Outputs |

Effluent, sewage sludge, possibly biogas (for some types)[1] |

| Types |

List of wastewater treatment technologies |

| Environmental concerns |

Water pollution, Environmental health, Public health, sewage sludge disposal issues |

Sewage treatment is a type of wastewater treatment which aims to remove contaminants from sewage to produce an effluent that is suitable to discharge to the surrounding environment or an intended reuse application, thereby preventing water pollution from raw sewage discharges.[2] Sewage contains wastewater from households and businesses and possibly pre-treated industrial wastewater. There are a large number of sewage treatment processes to choose from. These can range from decentralized systems (including on-site treatment systems) to large centralized systems involving a network of pipes and pump stations (called sewerage) which convey the sewage to a treatment plant. For cities that have a combined sewer, the sewers will also carry urban runoff (stormwater) to the sewage treatment plant. Sewage treatment often involves two main stages, called primary and secondary treatment, while advanced treatment also incorporates a tertiary treatment stage with polishing processes and nutrient removal. Secondary treatment can reduce organic matter (measured as biological oxygen demand) from sewage,  using aerobic or anaerobic biological processes. A so-called quaternary treatment step (sometimes referred to as advanced treatment) can also be added for the removal of organic micropollutants, such as pharmaceuticals. This has been implemented in full-scale for example in Sweden.[3]

A large number of sewage treatment technologies have been developed, mostly using biological treatment processes. Design engineers and decision makers need to take into account technical and economical criteria of each alternative when choosing a suitable technology.[4]: 215  Often, the main criteria for selection are desired effluent quality, expected construction and operating costs, availability of land, energy requirements and sustainability aspects. In developing countries and in rural areas with low population densities, sewage is often treated by various on-site sanitation systems and not conveyed in sewers. These systems include septic tanks connected to drain fields, on-site sewage systems (OSS), vermifilter systems and many more. On the other hand, advanced and relatively expensive sewage treatment plants may include tertiary treatment with disinfection and possibly even a fourth treatment stage to remove micropollutants.[3]

At the global level, an estimated 52% of sewage is treated.[5] However, sewage treatment rates are highly unequal for different countries around the world. For example, while high-income countries treat approximately 74% of their sewage, developing countries treat an average of just 4.2%.[5]

The treatment of sewage is part of the field of sanitation. Sanitation also includes the management of human waste and solid waste as well as stormwater (drainage) management.[6] The term sewage treatment plant is often used interchangeably with the term wastewater treatment plant.[4][page needed][7]

Terminology

[edit]

Activated sludge sewage treatment plant in Massachusetts, US

Activated sludge sewage treatment plant in Massachusetts, US

The term sewage treatment plant (STP) (or sewage treatment works) is nowadays often replaced with the term wastewater treatment plant (WWTP).[7][8] Strictly speaking, the latter is a broader term that can also refer to industrial wastewater treatment.

The terms water recycling center or water reclamation plants are also in use as synonyms.

Purposes and overview

[edit]

The overall aim of treating sewage is to produce an effluent that can be discharged to the environment while causing as little water pollution as possible, or to produce an effluent that can be reused in a useful manner.[9] This is achieved by removing contaminants from the sewage. It is a form of waste management.

With regards to biological treatment of sewage, the treatment objectives can include various degrees of the following: to transform or remove organic matter, nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus), pathogenic organisms, and specific trace organic constituents (micropollutants).[7]: 548

Some types of sewage treatment produce sewage sludge which can be treated before safe disposal or reuse. Under certain circumstances, the treated sewage sludge might be termed biosolids and can be used as a fertilizer.

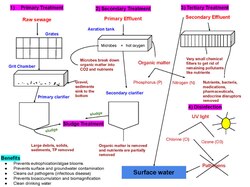

The process that raw sewage goes through before being released back into surface water

The process that raw sewage goes through before being released back into surface water

Sewage characteristics

[edit]

This section is an excerpt from Sewage § Concentrations and loads.[edit]

Typical values for physical–chemical characteristics of raw sewage in developing countries have been published as follows: 180 g/person/d for total solids (or 1100 mg/L when expressed as a concentration), 50 g/person/d for BOD (300 mg/L), 100 g/person/d for COD (600 mg/L), 8 g/person/d for total nitrogen (45 mg/L), 4.5 g/person/d for ammonia-N (25 mg/L) and 1.0 g/person/d for total phosphorus (7 mg/L).[10]: 57  The typical ranges for these values are: 120–220 g/person/d for total solids (or 700–1350 mg/L when expressed as a concentration), 40–60 g/person/d for BOD (250–400 mg/L), 80–120 g/person/d for COD (450–800 mg/L), 6–10 g/person/d for total nitrogen (35–60 mg/L), 3.5–6 g/person/d for ammonia-N (20–35 mg/L) and 0.7–2.5 g/person/d for total phosphorus (4–15 mg/L).[10]: 57

For high income countries, the "per person organic matter load" has been found to be approximately 60 gram of BOD per person per day.

[11] This is called the population equivalent (PE) and is also used as a comparison parameter to express the strength of industrial wastewater compared to sewage.

Collection

[edit]

This section is an excerpt from Sewerage.[edit]

Sewerage (or sewage system) is the infrastructure that conveys sewage or surface runoff (stormwater, meltwater, rainwater) using sewers. It encompasses components such as receiving drains, manholes, pumping stations, storm overflows, and screening chambers of the combined sewer or sanitary sewer. Sewerage ends at the entry to a sewage treatment plant or at the point of discharge into the environment. It is the system of pipes, chambers, manholes or inspection chamber, etc. that conveys the sewage or storm water.

In many cities, sewage (municipal wastewater or municipal sewage) is carried together with stormwater, in a combined sewer system, to a sewage treatment plant. In some urban areas, sewage is carried separately in sanitary sewers and runoff from streets is carried in storm drains. Access to these systems, for maintenance purposes, is typically through a manhole. During high precipitation periods a sewer system may experience a combined sewer overflow event or a sanitary sewer overflow event, which forces untreated sewage to flow directly to receiving waters. This can pose a serious threat to public health and the surrounding environment.

Types of treatment processes

[edit]

Sewage can be treated close to where the sewage is created, which may be called a decentralized system or even an on-site system (on-site sewage facility, septic tanks, etc.). Alternatively, sewage can be collected and transported by a network of pipes and pump stations to a municipal treatment plant. This is called a centralized system (see also sewerage and pipes and infrastructure).

A large number of sewage treatment technologies have been developed, mostly using biological treatment processes (see list of wastewater treatment technologies). Very broadly, they can be grouped into high tech (high cost) versus low tech (low cost) options, although some technologies might fall into either category. Other grouping classifications are intensive or mechanized systems (more compact, and frequently employing high tech options) versus extensive or natural or nature-based systems (usually using natural treatment processes and occupying larger areas) systems. This classification may be sometimes oversimplified, because a treatment plant may involve a combination of processes, and the interpretation of the concepts of high tech and low tech, intensive and extensive, mechanized and natural processes may vary from place to place.

Low tech, extensive or nature-based processes

[edit]

Constructed wetland (vertical flow) at Center for Research and Training in Sanitation, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Constructed wetland (vertical flow) at Center for Research and Training in Sanitation, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Trickling filter sewage treatment plant at Onça Treatment Plant, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Trickling filter sewage treatment plant at Onça Treatment Plant, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Examples for more low-tech, often less expensive sewage treatment systems are shown below. They often use little or no energy. Some of these systems do not provide a high level of treatment, or only treat part of the sewage (for example only the toilet wastewater), or they only provide pre-treatment, like septic tanks. On the other hand, some systems are capable of providing a good performance, satisfactory for several applications. Many of these systems are based on natural treatment processes, requiring large areas, while others are more compact. In most cases, they are used in rural areas or in small to medium-sized communities.

Rural Kansas lagoon on private property

Rural Kansas lagoon on private property

For example, waste stabilization ponds are a low cost treatment option with practically no energy requirements but they require a lot of land.[4]: 236  Due to their technical simplicity, most of the savings (compared with high tech systems) are in terms of operation and maintenance costs.[4]: 220–243

- Anaerobic digester types and anaerobic digestion, for example:

- Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket reactor

- Septic tank

- Imhoff tank

- Constructed wetland (see also biofilters)

- Decentralized wastewater system

- Nature-based solutions

- On-site sewage facility

- Sand filter

- Vermifilter

- Waste stabilization pond with sub-types:[4]: 189

- e.g. Facultative ponds, high rate ponds, maturation ponds

Examples for systems that can provide full or partial treatment for toilet wastewater only:

- Composting toilet (see also dry toilets in general)

- Urine-diverting dry toilet

- Vermifilter toilet

High tech, intensive or mechanized processes

[edit]

Aeration tank of activated sludge sewage treatment plant (fine-bubble diffusers) near Adelaide, Australia

Aeration tank of activated sludge sewage treatment plant (fine-bubble diffusers) near Adelaide, Australia

Examples for more high-tech, intensive or mechanized, often relatively expensive sewage treatment systems are listed below. Some of them are energy intensive as well. Many of them provide a very high level of treatment. For example, broadly speaking, the activated sludge process achieves a high effluent quality but is relatively expensive and energy intensive.[4]: 239

- Activated sludge systems

- Aerobic treatment system

- Enhanced biological phosphorus removal

- Expanded granular sludge bed digestion

- Filtration

- Membrane bioreactor

- Moving bed biofilm reactor

- Rotating biological contactor

- Trickling filter

- Ultraviolet disinfection

Disposal or treatment options

[edit]

There are other process options which may be classified as disposal options, although they can also be understood as basic treatment options. These include: Application of sludge, irrigation, soak pit, leach field, fish pond, floating plant pond, water disposal/groundwater recharge, surface disposal and storage.[12]: 138

The application of sewage to land is both: a type of treatment and a type of final disposal.[4]: 189  It leads to groundwater recharge and/or to evapotranspiration. Land application include slow-rate systems, rapid infiltration, subsurface infiltration, overland flow. It is done by flooding, furrows, sprinkler and dripping. It is a treatment/disposal system that requires a large amount of land per person.

Design aspects

[edit]

Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactor in Brazil (picture from a small-sized treatment plant), Center for Research and Training in Sanitation, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactor in Brazil (picture from a small-sized treatment plant), Center for Research and Training in Sanitation, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Population equivalent

[edit]

The per person organic matter load is a parameter used in the design of sewage treatment plants. This concept is known as population equivalent (PE). The base value used for PE can vary from one country to another. Commonly used definitions used worldwide are: 1 PE equates to 60 gram of BOD per person per day, and it also equals 200 liters of sewage per day.[13] This concept is also used as a comparison parameter to express the strength of industrial wastewater compared to sewage.

Process selection

[edit]

When choosing a suitable sewage treatment process, decision makers need to take into account technical and economical criteria.[4]: 215  Therefore, each analysis is site-specific. A life cycle assessment (LCA) can be used, and criteria or weightings are attributed to the various aspects. This makes the final decision subjective to some extent.[4]: 216  A range of publications exist to help with technology selection.[4]: 221 [12][14][15]

In industrialized countries, the most important parameters in process selection are typically efficiency, reliability, and space requirements. In developing countries, they might be different and the focus might be more on construction and operating costs as well as process simplicity.[4]: 218

Choosing the most suitable treatment process is complicated and requires expert inputs, often in the form of feasibility studies. This is because the main important factors to be considered when evaluating and selecting sewage treatment processes are numerous. They include: process applicability, applicable flow, acceptable flow variation, influent characteristics, inhibiting or refractory compounds, climatic aspects, process kinetics and reactor hydraulics, performance, treatment residuals, sludge processing, environmental constraints, requirements for chemical products, energy and other resources; requirements for personnel, operating and maintenance; ancillary processes, reliability, complexity, compatibility, area availability.[4]: 219

With regards to environmental impacts of sewage treatment plants the following aspects are included in the selection process: Odors, vector attraction, sludge transportation, sanitary risks, air contamination, soil and subsoil contamination, surface water pollution or groundwater contamination, devaluation of nearby areas, inconvenience to the nearby population.[4]: 220

Odor control

[edit]

Odors emitted by sewage treatment are typically an indication of an anaerobic or septic condition.[16] Early stages of processing will tend to produce foul-smelling gases, with hydrogen sulfide being most common in generating complaints. Large process plants in urban areas will often treat the odors with carbon reactors, a contact media with bio-slimes, small doses of chlorine, or circulating fluids to biologically capture and metabolize the noxious gases.[17] Other methods of odor control exist, including addition of iron salts, hydrogen peroxide, calcium nitrate, etc. to manage hydrogen sulfide levels.[18]

Energy requirements

[edit]

The energy requirements vary with type of treatment process as well as sewage strength. For example, constructed wetlands and stabilization ponds have low energy requirements.[19] In comparison, the activated sludge process has a high energy consumption because it includes an aeration step. Some sewage treatment plants produce biogas from their sewage sludge treatment process by using a process called anaerobic digestion. This process can produce enough energy to meet most of the energy needs of the sewage treatment plant itself.[7]: 1505

For activated sludge treatment plants in the United States, around 30 percent of the annual operating costs is usually required for energy.[7]: 1703  Most of this electricity is used for aeration, pumping systems and equipment for the dewatering and drying of sewage sludge. Advanced sewage treatment plants, e.g. for nutrient removal, require more energy than plants that only achieve primary or secondary treatment.[7]: 1704

Small rural plants using trickling filters may operate with no net energy requirements, the whole process being driven by gravitational flow, including tipping bucket flow distribution and the desludging of settlement tanks to drying beds. This is usually only practical in hilly terrain and in areas where the treatment plant is relatively remote from housing because of the difficulty in managing odors.[20][21]

Co-treatment of industrial effluent

[edit]

In highly regulated developed countries, industrial wastewater usually receives at least pretreatment if not full treatment at the factories themselves to reduce the pollutant load, before discharge to the sewer. The pretreatment has the following two main aims: Firstly, to prevent toxic or inhibitory compounds entering the biological stage of the sewage treatment plant and reduce its efficiency. And secondly to avoid toxic compounds from accumulating in the produced sewage sludge which would reduce its beneficial reuse options. Some industrial wastewater may contain pollutants which cannot be removed by sewage treatment plants. Also, variable flow of industrial waste associated with production cycles may upset the population dynamics of biological treatment units.[citation needed]

Design aspects of secondary treatment processes

[edit]

Main article: Secondary treatment § Design considerations

A poorly maintained anaerobic treatment pond in Kariba, Zimbabwe (sludge needs to be removed)

A poorly maintained anaerobic treatment pond in Kariba, Zimbabwe (sludge needs to be removed)

Non-sewered areas

[edit]

Urban residents in many parts of the world rely on on-site sanitation systems without sewers, such as septic tanks and pit latrines, and fecal sludge management in these cities is an enormous challenge.[22]

For sewage treatment the use of septic tanks and other on-site sewage facilities (OSSF) is widespread in some rural areas, for example serving up to 20 percent of the homes in the U.S.[23]

Available process steps

[edit]

Sewage treatment often involves two main stages, called primary and secondary treatment, while advanced treatment also incorporates a tertiary treatment stage with polishing processes.[13] Different types of sewage treatment may utilize some or all of the process steps listed below.

Preliminary treatment

[edit]

Preliminary treatment (sometimes called pretreatment) removes coarse materials that can be easily collected from the raw sewage before they damage or clog the pumps and sewage lines of primary treatment clarifiers.

Screening

[edit]

Preliminary treatment arrangement at small and medium-sized sewage treatment plants: Manually-cleaned screens and grit chamber (Jales Treatment Plant, São Paulo, Brazil)

Preliminary treatment arrangement at small and medium-sized sewage treatment plants: Manually-cleaned screens and grit chamber (Jales Treatment Plant, São Paulo, Brazil)

The influent in sewage water passes through a bar screen to remove all large objects like cans, rags, sticks, plastic packets, etc. carried in the sewage stream.[24] This is most commonly done with an automated mechanically raked bar screen in modern plants serving large populations, while in smaller or less modern plants, a manually cleaned screen may be used. The raking action of a mechanical bar screen is typically paced according to the accumulation on the bar screens and/or flow rate. The solids are collected and later disposed in a landfill, or incinerated. Bar screens or mesh screens of varying sizes may be used to optimize solids removal. If gross solids are not removed, they become entrained in pipes and moving parts of the treatment plant, and can cause substantial damage and inefficiency in the process.[25]: 9

Grit removal

[edit]

Preliminary treatment: Horizontal flow grit chambers at a sewage treatment plant in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Preliminary treatment: Horizontal flow grit chambers at a sewage treatment plant in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Grit consists of sand, gravel, rocks, and other heavy materials. Preliminary treatment may include a sand or grit removal channel or chamber, where the velocity of the incoming sewage is reduced to allow the settlement of grit. Grit removal is necessary to (1) reduce formation of deposits in primary sedimentation tanks, aeration tanks, anaerobic digesters, pipes, channels, etc. (2) reduce the frequency of tank cleaning caused by excessive accumulation of grit; and (3) protect moving mechanical equipment from abrasion and accompanying abnormal wear. The removal of grit is essential for equipment with closely machined metal surfaces such as comminutors, fine screens, centrifuges, heat exchangers, and high pressure diaphragm pumps.

Grit chambers come in three types: horizontal grit chambers, aerated grit chambers, and vortex grit chambers. Vortex grit chambers include mechanically induced vortex, hydraulically induced vortex, and multi-tray vortex separators. Given that traditionally, grit removal systems have been designed to remove clean inorganic particles that are greater than 0.210 millimetres (0.0083 in), most of the finer grit passes through the grit removal flows under normal conditions. During periods of high flow deposited grit is resuspended and the quantity of grit reaching the treatment plant increases substantially.[7]

Flow equalization

[edit]

Equalization basins can be used to achieve flow equalization. This is especially useful for combined sewer systems which produce peak dry-weather flows or peak wet-weather flows that are much higher than the average flows.[7]: 334  Such basins can improve the performance of the biological treatment processes and the secondary clarifiers.[7]: 334

Disadvantages include the basins' capital cost and space requirements. Basins can also provide a place to temporarily hold, dilute and distribute batch discharges of toxic or high-strength wastewater which might otherwise inhibit biological secondary treatment (such was wastewater from portable toilets or fecal sludge that is brought to the sewage treatment plant in vacuum trucks). Flow equalization basins require variable discharge control, typically include provisions for bypass and cleaning, and may also include aerators and odor control.[26]

Fat and grease removal

[edit]

In some larger plants, fat and grease are removed by passing the sewage through a small tank where skimmers collect the fat floating on the surface. Air blowers in the base of the tank may also be used to help recover the fat as a froth. Many plants, however, use primary clarifiers with mechanical surface skimmers for fat and grease removal.

Primary treatment

[edit]

Rectangular primary settling tanks at a sewage treatment plant in Oregon, US

Rectangular primary settling tanks at a sewage treatment plant in Oregon, US

Primary treatment is the "removal of a portion of the suspended solids and organic matter from the sewage".[7]: 11 It consists of allowing sewage to pass slowly through a basin where heavy solids can settle to the bottom while oil, grease and lighter solids float to the surface and are skimmed off. These basins are called primary sedimentation tanks or primary clarifiers and typically have a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 1.5 to 2.5 hours.[7]: 398  The settled and floating materials are removed and the remaining liquid may be discharged or subjected to secondary treatment. Primary settling tanks are usually equipped with mechanically driven scrapers that continually drive the collected sludge towards a hopper in the base of the tank where it is pumped to sludge treatment facilities.[25]: 9–11

Sewage treatment plants that are connected to a combined sewer system sometimes have a bypass arrangement after the primary treatment unit. This means that during very heavy rainfall events, the secondary and tertiary treatment systems can be bypassed to protect them from hydraulic overloading, and the mixture of sewage and storm-water receives primary treatment only.[27]

Primary sedimentation tanks remove about 50–70% of the suspended solids, and 25–40% of the biological oxygen demand (BOD).[7]: 396

Secondary treatment

[edit]

Main article: Secondary treatment

Simplified process flow diagram for a typical large-scale treatment plant using the activated sludge process

Simplified process flow diagram for a typical large-scale treatment plant using the activated sludge process

The main processes involved in secondary sewage treatment are designed to remove as much of the solid material as possible.[13] They use biological processes to digest and remove the remaining soluble material, especially the organic fraction. This can be done with either suspended-growth or biofilm processes. The microorganisms that feed on the organic matter present in the sewage grow and multiply, constituting the biological solids, or biomass. These grow and group together in the form of flocs or biofilms and, in some specific processes, as granules. The biological floc or biofilm and remaining fine solids form a sludge which can be settled and separated. After separation, a liquid remains that is almost free of solids, and with a greatly reduced concentration of pollutants.[13]

Secondary treatment can reduce organic matter (measured as biological oxygen demand) from sewage,  using aerobic or anaerobic processes. The organisms involved in these processes are sensitive to the presence of toxic materials, although these are not expected to be present at high concentrations in typical municipal sewage.

Tertiary treatment

[edit]

Overall setup for a micro filtration system

Overall setup for a micro filtration system

Advanced sewage treatment generally involves three main stages, called primary, secondary and tertiary treatment but may also include intermediate stages and final polishing processes. The purpose of tertiary treatment (also called advanced treatment) is to provide a final treatment stage to further improve the effluent quality before it is discharged to the receiving water body or reused. More than one tertiary treatment process may be used at any treatment plant. If disinfection is practiced, it is always the final process. It is also called effluent polishing. Tertiary treatment may include biological nutrient removal (alternatively, this can be classified as secondary treatment), disinfection and partly removal of micropollutants, such as environmental persistent pharmaceutical pollutants.

Tertiary treatment is sometimes defined as anything more than primary and secondary treatment in order to allow discharge into a highly sensitive or fragile ecosystem such as estuaries, low-flow rivers or coral reefs.[28] Treated water is sometimes disinfected chemically or physically (for example, by lagoons and microfiltration) prior to discharge into a stream, river, bay, lagoon or wetland, or it can be used for the irrigation of a golf course, greenway or park. If it is sufficiently clean, it can also be used for groundwater recharge or agricultural purposes.

Sand filtration removes much of the residual suspended matter.[25]: 22–23  Filtration over activated carbon, also called carbon adsorption, removes residual toxins.[25]: 19  Micro filtration or synthetic membranes are used in membrane bioreactors and can also remove pathogens.[7]: 854

Settlement and further biological improvement of treated sewage may be achieved through storage in large human-made ponds or lagoons. These lagoons are highly aerobic, and colonization by native macrophytes, especially reeds, is often encouraged.

Disinfection

[edit]

Disinfection of treated sewage aims to kill pathogens (disease-causing microorganisms) prior to disposal. It is increasingly effective after more elements of the foregoing treatment sequence have been completed.[29]: 359  The purpose of disinfection in the treatment of sewage is to substantially reduce the number of pathogens in the water to be discharged back into the environment or to be reused. The target level of reduction of biological contaminants like pathogens is often regulated by the presiding governmental authority. The effectiveness of disinfection depends on the quality of the water being treated (e.g. turbidity, pH, etc.), the type of disinfection being used, the disinfectant dosage (concentration and time), and other environmental variables. Water with high turbidity will be treated less successfully, since solid matter can shield organisms, especially from ultraviolet light or if contact times are low. Generally, short contact times, low doses and high flows all militate against effective disinfection. Common methods of disinfection include ozone, chlorine, ultraviolet light, or sodium hypochlorite.[25]: 16  Monochloramine, which is used for drinking water, is not used in the treatment of sewage because of its persistence.

Chlorination remains the most common form of treated sewage disinfection in many countries due to its low cost and long-term history of effectiveness. One disadvantage is that chlorination of residual organic material can generate chlorinated-organic compounds that may be carcinogenic or harmful to the environment. Residual chlorine or chloramines may also be capable of chlorinating organic material in the natural aquatic environment. Further, because residual chlorine is toxic to aquatic species, the treated effluent must also be chemically dechlorinated, adding to the complexity and cost of treatment.

Ultraviolet (UV) light can be used instead of chlorine, iodine, or other chemicals. Because no chemicals are used, the treated water has no adverse effect on organisms that later consume it, as may be the case with other methods. UV radiation causes damage to the genetic structure of bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens, making them incapable of reproduction. The key disadvantages of UV disinfection are the need for frequent lamp maintenance and replacement and the need for a highly treated effluent to ensure that the target microorganisms are not shielded from the UV radiation (i.e., any solids present in the treated effluent may protect microorganisms from the UV light). In many countries, UV light is becoming the most common means of disinfection because of the concerns about the impacts of chlorine in chlorinating residual organics in the treated sewage and in chlorinating organics in the receiving water.

As with UV treatment, heat sterilization also does not add chemicals to the water being treated. However, unlike UV, heat can penetrate liquids that are not transparent. Heat disinfection can also penetrate solid materials within wastewater, sterilizing their contents. Thermal effluent decontamination systems provide low resource, low maintenance effluent decontamination once installed.

Ozone (

O3) is generated by passing oxygen (

O2) through a high voltage potential resulting in a third oxygen atom becoming attached and forming

O3. Ozone is very unstable and reactive and oxidizes most organic material it comes in contact with, thereby destroying many pathogenic microorganisms. Ozone is considered to be safer than chlorine because, unlike chlorine which has to be stored on site (highly poisonous in the event of an accidental release), ozone is generated on-site as needed from the oxygen in the ambient air. Ozonation also produces fewer disinfection by-products than chlorination. A disadvantage of ozone disinfection is the high cost of the ozone generation equipment and the requirements for special operators. Ozone sewage treatment requires the use of an ozone generator, which decontaminates the water as ozone bubbles percolate through the tank.

Membranes can also be effective disinfectants, because they act as barriers, avoiding the passage of the microorganisms. As a result, the final effluent may be devoid of pathogenic organisms, depending on the type of membrane used. This principle is applied in membrane bioreactors.

Biological nutrient removal

[edit]

Nitrification process tank at an activated sludge plant in the United States

Nitrification process tank at an activated sludge plant in the United States

Sewage may contain high levels of the nutrients nitrogen and phosphorus. Typical values for nutrient loads per person and nutrient concentrations in raw sewage in developing countries have been published as follows: 8 g/person/d for total nitrogen (45 mg/L), 4.5 g/person/d for ammonia-N (25 mg/L) and 1.0 g/person/d for total phosphorus (7 mg/L).[4]: 57  The typical ranges for these values are: 6–10 g/person/d for total nitrogen (35–60 mg/L), 3.5–6 g/person/d for ammonia-N (20–35 mg/L) and 0.7–2.5 g/person/d for total phosphorus (4–15 mg/L).[4]: 57

Excessive release to the environment can lead to nutrient pollution, which can manifest itself in eutrophication. This process can lead to algal blooms, a rapid growth, and later decay, in the population of algae. In addition to causing deoxygenation, some algal species produce toxins that contaminate drinking water supplies.

Ammonia nitrogen, in the form of free ammonia (NH3) is toxic to fish. Ammonia nitrogen, when converted to nitrite and further to nitrate in a water body, in the process of nitrification, is associated with the consumption of dissolved oxygen. Nitrite and nitrate may also have public health significance if concentrations are high in drinking water, because of a disease called metahemoglobinemia.[4]: 42

Phosphorus removal is important as phosphorus is a limiting nutrient for algae growth in many fresh water systems. Therefore, an excess of phosphorus can lead to eutrophication. It is also particularly important for water reuse systems where high phosphorus concentrations may lead to fouling of downstream equipment such as reverse osmosis.

A range of treatment processes are available to remove nitrogen and phosphorus. Biological nutrient removal (BNR) is regarded by some as a type of secondary treatment process,[7] and by others as a tertiary (or advanced) treatment process.

Nitrogen removal

[edit]

Constructed wetlands (vertical flow) for sewage treatment near Shanghai, China

Constructed wetlands (vertical flow) for sewage treatment near Shanghai, China

Nitrogen is removed through the biological oxidation of nitrogen from ammonia to nitrate (nitrification), followed by denitrification, the reduction of nitrate to nitrogen gas. Nitrogen gas is released to the atmosphere and thus removed from the water.

Nitrification itself is a two-step aerobic process, each step facilitated by a different type of bacteria. The oxidation of ammonia (NH4+) to nitrite (NO2−) is most often facilitated by bacteria such as Nitrosomonas spp. (nitroso refers to the formation of a nitroso functional group). Nitrite oxidation to nitrate (NO3−), though traditionally believed to be facilitated by Nitrobacter spp. (nitro referring the formation of a nitro functional group), is now known to be facilitated in the environment predominantly by Nitrospira spp.

Denitrification requires anoxic conditions to encourage the appropriate biological communities to form. Anoxic conditions refers to a situation where oxygen is absent but nitrate is present. Denitrification is facilitated by a wide diversity of bacteria. The activated sludge process, sand filters, waste stabilization ponds, constructed wetlands and other processes can all be used to reduce nitrogen.[25]: 17–18  Since denitrification is the reduction of nitrate to dinitrogen (molecular nitrogen) gas, an electron donor is needed. This can be, depending on the wastewater, organic matter (from the sewage itself), sulfide, or an added donor like methanol. The sludge in the anoxic tanks (denitrification tanks) must be mixed well (mixture of recirculated mixed liquor, return activated sludge, and raw influent) e.g. by using submersible mixers in order to achieve the desired denitrification.

Over time, different treatment configurations for activated sludge processes have evolved to achieve high levels of nitrogen removal. An initial scheme was called the Ludzack–Ettinger Process. It could not achieve a high level of denitrification.[7]: 616  The Modified Ludzak–Ettinger Process (MLE) came later and was an improvement on the original concept. It recycles mixed liquor from the discharge end of the aeration tank to the head of the anoxic tank. This provides nitrate for the facultative bacteria.[7]: 616

There are other process configurations, such as variations of the Bardenpho process.[30]: 160  They might differ in the placement of anoxic tanks, e.g. before and after the aeration tanks.

Phosphorus removal

[edit]

Studies of United States sewage in the late 1960s estimated mean per capita contributions of 500 grams (18 oz) in urine and feces, 1,000 grams (35 oz) in synthetic detergents, and lesser variable amounts used as corrosion and scale control chemicals in water supplies.[31] Source control via alternative detergent formulations has subsequently reduced the largest contribution, but naturally the phosphorus content of urine and feces remained unchanged.

Phosphorus can be removed biologically in a process called enhanced biological phosphorus removal. In this process, specific bacteria, called polyphosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs), are selectively enriched and accumulate large quantities of phosphorus within their cells (up to 20 percent of their mass).[30]: 148–155

Phosphorus removal can also be achieved by chemical precipitation, usually with salts of iron (e.g. ferric chloride) or aluminum (e.g. alum), or lime.[25]: 18  This may lead to a higher sludge production as hydroxides precipitate and the added chemicals can be expensive. Chemical phosphorus removal requires significantly smaller equipment footprint than biological removal, is easier to operate and is often more reliable than biological phosphorus removal. Another method for phosphorus removal is to use granular laterite or zeolite.[32][33]

Some systems use both biological phosphorus removal and chemical phosphorus removal. The chemical phosphorus removal in those systems may be used as a backup system, for use when the biological phosphorus removal is not removing enough phosphorus, or may be used continuously. In either case, using both biological and chemical phosphorus removal has the advantage of not increasing sludge production as much as chemical phosphorus removal on its own, with the disadvantage of the increased initial cost associated with installing two different systems.

Once removed, phosphorus, in the form of a phosphate-rich sewage sludge, may be sent to landfill or used as fertilizer in admixture with other digested sewage sludges. In the latter case, the treated sewage sludge is also sometimes referred to as biosolids. 22% of the world's phosphorus needs could be satisfied by recycling residential wastewater.[34][35]

Fourth treatment stage

[edit]

Further information: Environmental impact of pharmaceuticals and personal care products

Micropollutants such as pharmaceuticals, ingredients of household chemicals, chemicals used in small businesses or industries, environmental persistent pharmaceutical pollutants (EPPP) or pesticides may not be eliminated in the commonly used sewage treatment processes (primary, secondary and tertiary treatment) and therefore lead to water pollution.[36] Although concentrations of those substances and their decomposition products are quite low, there is still a chance of harming aquatic organisms. For pharmaceuticals, the following substances have been identified as toxicologically relevant: substances with endocrine disrupting effects, genotoxic substances and substances that enhance the development of bacterial resistances.[37] They mainly belong to the group of EPPP.

Techniques for elimination of micropollutants via a fourth treatment stage during sewage treatment are implemented in Germany, Switzerland, Sweden[3] and the Netherlands and tests are ongoing in several other countries.[38] In Switzerland it has been enshrined in law since 2016.[39] Since 1 January 2025, there has been a recast of the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive in the European Union. Due to the large number of amendments that have now been made, the directive was rewritten on November 27, 2024 as Directive (EU) 2024/3019, published in the EU Official Journal on December 12, and entered into force on January 1, 2025. The member states now have 31 months, i.e. until July 31, 2027, to adapt their national legislation to the new directive ("implementation of the directive").

The amendment stipulates that, in addition to stricter discharge values for nitrogen and phosphorus, persistent trace substances must at least be partially separated. The target, similar to Switzerland, is that 80% of 6 key substances out of 12 must be removed between discharge into the sewage treatment plant and discharge into the water body. At least 80% of the investments and operating costs for the fourth treatment stage will be passed on to the pharmaceutical and cosmetics industry according to the polluter pays principle in order to relieve the population financially and provide an incentive for the development of more environmentally friendly products. In addition, the municipal wastewater treatment sector is to be energy neutral by 2045 and the emission of microplastics and PFAS is to be monitored.

The implementation of the framework guidelines is staggered until 2045, depending on the size of the sewage treatment plant and its population equivalents (PE). Sewage treatment plants with over 150,000 PE have priority and should be adapted immediately, as a significant proportion of the pollution comes from them. The adjustments are staggered at national level in:

- 20% of the plants by 31 December 2033,

- 60% of the plants by 31 December 2039,

- 100% of the plants by 31 December 2045.

Wastewater treatment plants with 10,000 to 150,000 PE that discharge into coastal waters or sensitive waters are staggered at national level in:

- 10% of the plants by 31 December 2033,

- 30% of the plants by 31 December 2036,

- 60% of the plants by 31 December 2039,

- 100% of the plants by 31 December 2045.

The latter concerns waters with a low dilution ratio, waters from which drinking water is obtained and those that are coastal waters, or those used as bathing waters or used for mussel farming. Member States will be given the option not to apply fourth treatment in these areas if a risk assessment shows that there is no potential risk from micropollutants to human health and/or the environment.[40][41]

Such process steps mainly consist of activated carbon filters that adsorb the micropollutants. The combination of advanced oxidation with ozone followed by granular activated carbon (GAC) has been suggested as a cost-effective treatment combination for pharmaceutical residues. For a full reduction of microplasts the combination of ultrafiltration followed by GAC has been suggested. Also the use of enzymes such as laccase secreted by fungi is under investigation.[42][43] Microbial biofuel cells are investigated for their property to treat organic matter in sewage.[44]

To reduce pharmaceuticals in water bodies, source control measures are also under investigation, such as innovations in drug development or more responsible handling of drugs.[37][45] In the US, the National Take Back Initiative is a voluntary program with the general public, encouraging people to return excess or expired drugs, and avoid flushing them to the sewage system.[46]

Sludge treatment and disposal

[edit]

View of a belt filter press at the Blue Plains Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant, Washington, D.C.

View of a belt filter press at the Blue Plains Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant, Washington, D.C.

Mechanical dewatering of sewage sludge with a centrifuge at a large sewage treatment plant (Arrudas Treatment Plant, Belo Horizonte, Brazil)

Mechanical dewatering of sewage sludge with a centrifuge at a large sewage treatment plant (Arrudas Treatment Plant, Belo Horizonte, Brazil)

This section is an excerpt from Sewage sludge treatment.[edit]

Sewage sludge treatment describes the processes used to manage and dispose of sewage sludge produced during sewage treatment. Sludge treatment is focused on reducing sludge weight and volume to reduce transportation and disposal costs, and on reducing potential health risks of disposal options. Water removal is the primary means of weight and volume reduction, while pathogen destruction is frequently accomplished through heating during thermophilic digestion, composting, or incineration. The choice of a sludge treatment method depends on the volume of sludge generated, and comparison of treatment costs required for available disposal options. Air-drying and composting may be attractive to rural communities, while limited land availability may make aerobic digestion and mechanical dewatering preferable for cities, and economies of scale may encourage energy recovery alternatives in metropolitan areas.

Sludge is mostly water with some amounts of solid material removed from liquid sewage. Primary sludge includes settleable solids removed during primary treatment in primary clarifiers. Secondary sludge is sludge separated in secondary clarifiers that are used in secondary treatment bioreactors or processes using inorganic oxidizing agents. In intensive sewage treatment processes, the sludge produced needs to be removed from the liquid line on a continuous basis because the volumes of the tanks in the liquid line have insufficient volume to store sludge.[47] This is done in order to keep the treatment processes compact and in balance (production of sludge approximately equal to the removal of sludge). The sludge removed from the liquid line goes to the sludge treatment line. Aerobic processes (such as the activated sludge process) tend to produce more sludge compared with anaerobic processes. On the other hand, in extensive (natural) treatment processes, such as ponds and constructed wetlands, the produced sludge remains accumulated in the treatment units (liquid line) and is only removed after several years of operation.[48]

Sludge treatment options depend on the amount of solids generated and other site-specific conditions. Composting is most often applied to small-scale plants with aerobic digestion for mid-sized operations, and anaerobic digestion for the larger-scale operations. The sludge is sometimes passed through a so-called pre-thickener which de-waters the sludge. Types of pre-thickeners include centrifugal sludge thickeners,

[49] rotary drum sludge thickeners and belt filter presses.

[50] Dewatered sludge may be incinerated or transported offsite for disposal in a landfill or use as an agricultural soil amendment.

[51]

Environmental impacts

[edit]

Sewage treatment plants can have significant effects on the biotic status of receiving waters and can cause some water pollution, especially if the treatment process used is only basic. For example, for sewage treatment plants without nutrient removal, eutrophication of receiving water bodies can be a problem.

This section is an excerpt from Water pollution.[edit]

Water pollution (or aquatic pollution) is the contamination of water bodies, with a negative impact on their uses.

[52]: 6  It is usually a result of human activities. Water bodies include lakes, rivers, oceans, aquifers, reservoirs and groundwater. Water pollution results when contaminants mix with these water bodies. Contaminants can come from one of four main sources. These are sewage discharges, industrial activities, agricultural activities, and urban runoff including stormwater.

[53] Water pollution may affect either surface water or groundwater. This form of pollution can lead to many problems. One is the degradation of aquatic ecosystems. Another is spreading water-borne diseases when people use polluted water for drinking or irrigation.

[54] Water pollution also reduces the ecosystem services such as drinking water provided by the water resource.

Treated effluent from sewage treatment plant in DÄ›Äín, Czech Republic, is discharged to surface waters.

Treated effluent from sewage treatment plant in DÄ›Äín, Czech Republic, is discharged to surface waters.

In 2024, The Royal Academy of Engineering released a study into the effects wastewater on public health in the United Kingdom.[55] The study gained media attention, with comments from the UKs leading health professionals, including Sir Chris Whitty. Outlining 15 recommendations for various UK bodies to dramatically reduce public health risks by increasing the water quality in its waterways, such as rivers and lakes.

After the release of the report, The Guardian newspaper interviewed Whitty, who stated that improving water quality and sewage treatment should be a high level of importance and a "public health priority". He compared it to eradicating cholera in the 19th century in the country following improvements to the sewage treatment network.[56] The study also identified that low water flows in rivers saw high concentration levels of sewage, as well as times of flooding or heavy rainfall. While heavy rainfall had always been associated with sewage overflows into streams and rivers, the British media went as far to warn parents of the dangers of paddling in shallow rivers during warm weather.[57]

Whitty's comments came after the study revealed that the UK was experiencing a growth in the number of people that were using coastal and inland waters recreationally. This could be connected to a growing interest in activities such as open water swimming or other water sports.[58] Despite this growth in recreation, poor water quality meant some were becoming unwell during events.[59] Most notably, the 2024 Paris Olympics had to delay numerous swimming-focused events like the triathlon due to high levels of sewage in the River Seine.[60]

Reuse

[edit]

Further information: Reuse of excreta

Sludge drying beds for sewage sludge treatment at a small treatment plant at the Center for Research and Training in Sanitation, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Sludge drying beds for sewage sludge treatment at a small treatment plant at the Center for Research and Training in Sanitation, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Irrigation

[edit]

See also: Sewage farm

Increasingly, people use treated or even untreated sewage for irrigation to produce crops. Cities provide lucrative markets for fresh produce, so are attractive to farmers. Because agriculture has to compete for increasingly scarce water resources with industry and municipal users, there is often no alternative for farmers but to use water polluted with sewage directly to water their crops. There can be significant health hazards related to using water loaded with pathogens in this way. The World Health Organization developed guidelines for safe use of wastewater in 2006.[61] They advocate a 'multiple-barrier' approach to wastewater use, where farmers are encouraged to adopt various risk-reducing behaviors. These include ceasing irrigation a few days before harvesting to allow pathogens to die off in the sunlight, applying water carefully so it does not contaminate leaves likely to be eaten raw, cleaning vegetables with disinfectant or allowing fecal sludge used in farming to dry before being used as a human manure.[62]

Circular secondary sedimentation tank at activated sludge sewage treatment plant at Arrudas Treatment Plant, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Circular secondary sedimentation tank at activated sludge sewage treatment plant at Arrudas Treatment Plant, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Reclaimed water

[edit]

This section is an excerpt from Reclaimed water.[edit]

Water reclamation is the process of converting municipal wastewater or sewage and industrial wastewater into water that can be reused for a variety of purposes. It is also called wastewater reuse, water reuse or water recycling. There are many types of reuse. It is possible to reuse water in this way in cities or for irrigation in agriculture. Other types of reuse are environmental reuse, industrial reuse, and reuse for drinking water, whether planned or not. Reuse may include irrigation of gardens and agricultural fields or replenishing surface water and groundwater. This latter is also known as groundwater recharge. Reused water also serve various needs in residences such as toilet flushing, businesses, and industry. It is possible to treat wastewater to reach drinking water standards. Injecting reclaimed water into the water supply distribution system is known as direct potable reuse. Drinking reclaimed water is not typical.[63] Reusing treated municipal wastewater for irrigation is a long-established practice. This is especially so in arid countries. Reusing wastewater as part of sustainable water management allows water to remain an alternative water source for human activities. This can reduce scarcity. It also eases pressures on groundwater and other natural water bodies.[64]

Global situation

[edit]

Share of domestic wastewater that is safely treated (in 2018)[65]

Share of domestic wastewater that is safely treated (in 2018)[65]

Before the 20th century in Europe, sewers usually discharged into a body of water such as a river, lake, or ocean. There was no treatment, so the breakdown of the human waste was left to the ecosystem. This could lead to satisfactory results if the assimilative capacity of the ecosystem is sufficient which is nowadays not often the case due to increasing population density.[4]: 78

Today, the situation in urban areas of industrialized countries is usually that sewers route their contents to a sewage treatment plant rather than directly to a body of water. In many developing countries, however, the bulk of municipal and industrial wastewater is discharged to rivers and the ocean without any treatment or after preliminary treatment or primary treatment only. Doing so can lead to water pollution. Few reliable figures exist on the share of the wastewater collected in sewers that is being treated worldwide. A global estimate by UNDP and UN-Habitat in 2010 was that 90% of all wastewater generated is released into the environment untreated.[66] A more recent study in 2021 estimated that globally, about 52% of sewage is treated.[5] However, sewage treatment rates are highly unequal for different countries around the world. For example, while high-income countries treat approximately 74% of their sewage, developing countries treat an average of just 4.2%.[5] As of 2022, without sufficient treatment, more than 80% of all wastewater generated globally is released into the environment. High-income nations treat, on average, 70% of the wastewater they produce, according to UN Water.[34][67][68] Only 8% of wastewater produced in low-income nations receives any sort of treatment.[34][69][70]

The Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) for Water Supply and Sanitation by WHO and UNICEF report in 2021 that 82% of people with sewer connections are connected to sewage treatment plants providing at least secondary treatment.[71]: 55 However, this value varies widely between regions. For example, in Europe, North America, Northern Africa and Western Asia, a total of 31 countries had universal (>99%) wastewater treatment. However, in Albania, Bermuda, North Macedonia and Serbia "less than 50% of sewered wastewater received secondary or better treatment" and in Algeria, Lebanon and Libya the value was less than 20% of sewered wastewater that was being treated. The report also found that "globally, 594 million people have sewer connections that don't receive sufficient treatment. Many more are connected to wastewater treatment plants that do not provide effective treatment or comply with effluent requirements.".[71]: 55

Global targets

[edit]

Sustainable Development Goal 6 has a Target 6.3 which is formulated as follows: "By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating,dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally."[65] The corresponding Indicator 6.3.1 is the "proportion of wastewater safely treated". It is anticipated that wastewater production would rise by 24% by 2030 and by 51% by 2050.[34][72][73]

Data in 2020 showed that there is still too much uncollected household wastewater: Only 66% of all household wastewater flows were collected at treatment facilities in 2020 (this is determined from data from 128 countries).[8]: 17  Based on data from 42 countries in 2015, the report stated that "32 per cent of all wastewater flows generated from point sources received at least some treatment".[8]: 17  For sewage that has indeed been collected at centralized sewage treatment plants, about 79% went on to be safely treated in 2020.[8]: 18

History

[edit]

Further information: History of water supply and sanitation § Sewage treatment

The history of sewage treatment had the following developments: It began with land application (sewage farms) in the 1840s in England, followed by chemical treatment and sedimentation of sewage in tanks, then biological treatment in the late 19th century, which led to the development of the activated sludge process starting in 1912.[74][75]

This section is an excerpt from History of water supply and sanitation § Biological treatment.[edit]

It was not until the late 19th century that it became possible to treat the sewage by biologically decomposing the organic components through the use of microorganisms and removing the pollutants. Land treatment was also steadily becoming less feasible, as cities grew and the volume of sewage produced could no longer be absorbed by the farmland on the outskirts.

Edward Frankland conducted experiments at the sewage farm in Croydon, England during the 1870s and was able to demonstrate that filtration of sewage through porous gravel produced a nitrified effluent (the ammonia was converted into nitrate) and that the filter remained unclogged over long periods of time.[76] This established the then revolutionary possibility of biological treatment of sewage using a contact bed to oxidize the waste. This concept was taken up by the chief chemist for the London Metropolitan Board of Works, William Dibdin, in 1887:

- ...in all probability the true way of purifying sewage...will be first to separate the sludge, and then turn into neutral effluent... retain it for a sufficient period, during which time it should be fully aerated, and finally discharge it into the stream in a purified condition. This is indeed what is aimed at and imperfectly accomplished on a sewage farm.[77]

From 1885 to 1891, filters working on Dibdin's principle were constructed throughout the UK and the idea was also taken up in the US at the Lawrence Experiment Station in Massachusetts, where Frankland's work was confirmed.

[78] In 1890, the LES developed a 'trickling filter' that gave a much more reliable performance.

[79]

Regulations

[edit]

In most countries, sewage collection and treatment are subject to local and national regulations and standards.

By country

[edit]

Overview

[edit]

Wastewater treatment by country

| |

- Benin

- China

- Costa Rica

- Egypt

- Ireland

- Jordan

- Morocco

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Peru

- Portugal

- South Africa

- Uganda

- Yemen

|

Water supply and sanitation by country

Europe

[edit]

In the European Union, 0.8% of total energy consumption goes to wastewater treatment facilities.[34][80] The European Union needs to make extra investments of €90 billion in the water and waste sector to meet its 2030 climate and energy goals.[34][81][82]

In October 2021, British Members of Parliament voted to continue allowing untreated sewage from combined sewer overflows to be released into waterways.[83][84]

This section is an excerpt from Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive § Description.[edit]

The Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive (full title "Council Directive 91/271/EEC of 21 May 1991 concerning urban waste-water treatment") is a European Union directive regarding urban wastewater collection, wastewater treatment and its discharge, as well as the treatment and discharge of "waste water from certain industrial sectors". It was adopted on 21 May 1991.[85] It aims "to protect the environment from the adverse effects of urban waste water discharges and discharges from certain industrial sectors" by mandating waste water collection and treatment in urban agglomerations with a population equivalent of over 2000, and more advanced treatment in places with a population equivalent above 10,000 in sensitive areas.[86]

Asia

[edit]

India

[edit]

This section is an excerpt from Water supply and sanitation in India § Wastewater treatment.[edit]

Picture of a wastewater stream

Picture of a wastewater stream

In India, wastewater treatment regulations come under three central institutions, the ministries of forest, climate change housing, urban affairs and water.

[87] The various water and sanitation policies such as the "National Environment Policy 2006" and "National Sanitation Policy 2008" also lay down wastewater treatment regulations. State governments and local municipalities hold responsibility for the disposal of sewage and construction and maintenance of "sewerage infrastructure". Their efforts are supported by schemes offered by the Government of India, such as the National River Conservation Plan, Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, National Lake Conservation Plan. Through the Ministry of Environment and Forest, India's government also has set up incentives that encourage industries to establish "common facilities" to undertake the treatment of wastewater.

[88]

The 'Delhi Jal Board' (DJB) is currently operating on the construction of the largest sewage treatment plant in India. It will be operational by the end of 2022 with an estimated capacity of 564 MLD. It is supposed to solve the existing situation wherein untreated sewage water is being discharged directly into the river 'Yamuna'.

Japan

[edit]

This section is an excerpt from Water supply and sanitation in Japan § Wastewater treatment and sanitation.[edit]

Currently, Japan's methods of wastewater treatment include rural community sewers, wastewater facilities, and on-site treatment systems such as the Johkasou system to treat domestic wastewater.[89] Larger wastewater facilities and sewer systems are generally used to treat wastewater in more urban areas with a larger population. Rural sewage systems are used to treat wastewater at smaller domestic wastewater treatment plants for a smaller population. Johkasou systems are on-site wastewater treatment systems tanks. They are used to treat the wastewater of a single household or to treat the wastewater of a small number of buildings in a more decentralized manner than a sewer system.[90]

Africa

[edit]

Libya

[edit]

This section is an excerpt from Environmental issues in Libya § Wastewater treatment.[edit]

In Libya, municipal wastewater treatment is managed by the general company for water and wastewater in Libya, which falls within the competence of the Housing and Utilities Government Ministry. There are approximately 200 sewage treatment plants across the nation, but few plants are functioning. In fact, the 36 larger plants are in the major cities; however, only nine of them are operational, and the rest of them are under repair.[91]

The largest operating wastewater treatment plants are situated in Sirte, Tripoli, and Misurata, with a design capacity of 21,000, 110,000, and 24,000 m3/day, respectively. Moreover, a majority of the remaining wastewater facilities are small and medium-sized plants with a design capacity of approximately 370 to 6700 m3/day. Therefore, 145,800 m3/day or 11 percent of the wastewater is actually treated, and the remaining others are released into the ocean and artificial lagoons although they are untreated. In fact, nonoperational wastewater treatment plants in Tripoli lead to a spill of over 1,275, 000 cubic meters of unprocessed water into the ocean every day.

[91]

Americas

[edit]

United States

[edit]

This section is an excerpt from Water supply and sanitation in the United States § Wastewater treatment.[edit]

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and state environmental agencies set wastewater standards under the Clean Water Act.[92] Point sources must obtain surface water discharge permits through the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES). Point sources include industrial facilities, municipal governments (sewage treatment plants and storm sewer systems), other government facilities such as military bases, and some agricultural facilities, such as animal feedlots.[93] EPA sets basic national wastewater standards: The "Secondary Treatment Regulation" applies to municipal sewage treatment plants,[94] and the "Effluent guidelines" which are regulations for categories of industrial facilities.[95]

See also

[edit]

Environment portal

Environment portal

- Decentralized wastewater system

- List of largest wastewater treatment plants

- List of water supply and sanitation by country

- Organisms involved in water purification

- Sanitary engineering

- Waste disposal

References

[edit]

- ^ a b c

"Sanitation Systems – Sanitation Technologies – Activated sludge". SSWM. 27 April 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ Khopkar, S.M. (2004). Environmental Pollution Monitoring And Control. New Delhi: New Age International. p. 299. ISBN 978-81-224-1507-0.

- ^ a b c Takman, Maria; Svahn, Ola; Paul, Catherine; Cimbritz, Michael; Blomqvist, Stefan; Struckmann Poulsen, Jan; Lund Nielsen, Jeppe; Davidsson, Åsa (15 October 2023). "Assessing the potential of a membrane bioreactor and granular activated carbon process for wastewater reuse – A full-scale WWTP operated over one year in Scania, Sweden". Science of the Total Environment. 895: 165185. Bibcode:2023ScTEn.89565185T. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165185. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 37385512. S2CID 259296091.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Von Sperling, M. (2007). "Wastewater Characteristics, Treatment and Disposal". Water Intelligence Online. 6. doi:10.2166/9781780402086. ISSN 1476-1777.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ a b c d Jones, Edward R.; van Vliet, Michelle T. H.; Qadir, Manzoor; Bierkens, Marc F. P. (2021). "Country-level and gridded estimates of wastewater production, collection, treatment and reuse". Earth System Science Data. 13 (2): 237–254. Bibcode:2021ESSD...13..237J. doi:10.5194/essd-13-237-2021. ISSN 1866-3508.

- ^ "Sanitation". Health topics. World Health Organization. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p George Tchobanoglous; H. David Stensel; Ryujiro Tsuchihashi; Franklin L. Burton; Mohammad Abu-Orf; Gregory Bowden, eds. (2014). Metcalf & Eddy Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Resource Recovery (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-340118-8. OCLC 858915999.

- ^ a b c d UN-Water, 2021: Summary Progress Update 2021 – SDG 6 – water and sanitation for all. Version: July 2021. Geneva, Switzerland

- ^ WWAP (United Nations World Water Assessment Programme) (2017). The United Nations World Water Development Report 2017. Wastewater: The Untapped Resource. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100201-4. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017.

- ^ a b Von Sperling, M. (2007). "Wastewater Characteristics, Treatment and Disposal". Water Intelligence Online. 6. doi:10.2166/9781780402086. ISBN 978-1-78040-208-6. ISSN 1476-1777.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ Henze, M.; van Loosdrecht, M. C. M.; Ekama, G.A.; Brdjanovic, D. (2008). Biological Wastewater Treatment: Principles, Modelling and Design. IWA Publishing. doi:10.2166/9781780401867. ISBN 978-1-78040-186-7. S2CID 108595515. Spanish and Arabic versions available free online

- ^ a b Tilley E, Ulrich L, Lüthi C, Reymond P, Zurbrügg C (2014). Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies (2nd Revised ed.). Duebendorf, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag). ISBN 978-3-906484-57-0. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d Henze, M.; van Loosdrecht, M. C. M.; Ekama, G.A.; Brdjanovic, D. (2008). Biological Wastewater Treatment: Principles, Modelling and Design. IWA Publishing. doi:10.2166/9781780401867. ISBN 978-1-78040-186-7. S2CID 108595515. (Spanish and Arabic versions are available online for free)

- ^ Spuhler, Dorothee; Germann, Verena; Kassa, Kinfe; Ketema, Atekelt Abebe; Sherpa, Anjali Manandhar; Sherpa, Mingma Gyalzen; Maurer, Max; Lüthi, Christoph; Langergraber, Guenter (2020). "Developing sanitation planning options: A tool for systematic consideration of novel technologies and systems". Journal of Environmental Management. 271: 111004. Bibcode:2020JEnvM.27111004S. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111004. hdl:20.500.11850/428109. PMID 32778289. S2CID 221100596.

- ^ Spuhler, Dorothee; Scheidegger, Andreas; Maurer, Max (2020). "Comparative analysis of sanitation systems for resource recovery: Influence of configurations and single technology components". Water Research. 186: 116281. Bibcode:2020WatRe.18616281S. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2020.116281. PMID 32949886. S2CID 221806742.

- ^ Harshman, Vaughan; Barnette, Tony (28 December 2000). "Wastewater Odor Control: An Evaluation of Technologies". Water Engineering & Management. ISSN 0273-2238.

- ^ Walker, James D. and Welles Products Corporation (1976)."Tower for removing odors from gases." U.S. Patent No. 4421534.

- ^ Sercombe, Derek C. W. (April 1985). "The control of septicity and odours in sewerage systems and at sewage treatment works operated by Anglian Water Services Limited". Water Science & Technology. 31 (7): 283–292. doi:10.2166/wst.1995.0244.

- ^ Hoffmann, H., Platzer, C., von Münch, E., Winker, M. (2011). Technology review of constructed wetlands – Subsurface flow constructed wetlands for greywater and domestic wastewater treatment. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Eschborn, Germany, p. 11

- ^ Galvão, A; Matos, J; Rodrigues, J; Heath, P (1 December 2005). "Sustainable sewage solutions for small agglomerations". Water Science & Technology. 52 (12): 25–32. Bibcode:2005WSTec..52R..25G. doi:10.2166/wst.2005.0420. PMID 16477968. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "Wastewater Treatment Plant - Operator Certification Training - Module 20:Trickling Filter" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Chowdhry, S., Koné, D. (2012). Business Analysis of Fecal Sludge Management: Emptying and Transportation Services in Africa and Asia – Draft final report. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, US

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C. (2008). "Septic Systems Fact Sheet." Archived 12 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine EPA publication no. 832-F-08-057.

- ^ Water and Environmental Health at London and Loughborough (1999). "Waste water Treatment Options." Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine Technical brief no. 64. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and Loughborough University.

- ^ a b c d e f g EPA. Washington, DC (2004). "Primer for Municipal Waste water Treatment Systems." Document no. EPA 832-R-04-001.

- ^ "Chapter 3. Flow Equalization". Process Design Manual for Upgrading Existing Wastewater Treatment Plants (Report). EPA. October 1971.

- ^ "How Wastewater Treatment Works...The Basics" (PDF). EPA. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2024. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "Stage 3 - Tertiary treatment". Sydney Water. 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Metcalf & Eddy, Inc. (1972). Wastewater Engineering. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-041675-8.

- ^ a b Von Sperling, M. (30 December 2015). "Activated Sludge and Aerobic Biofilm Reactors". Water Intelligence Online. 6: 9781780402123. doi:10.2166/9781780402123. ISSN 1476-1777.

- ^ Process Design Manual for Phosphorus Removal (Report). EPA. 1976. pp. 2–1. EPA 625/1-76-001a.

- ^ Wood, R. B.; McAtamney, C.F. (December 1996). "Constructed wetlands for waste water treatment: the use of laterite in the bed medium in phosphorus and heavy metal removal". Hydrobiologia. 340 (1–3): 323–331. Bibcode:1996HyBio.340..323W. doi:10.1007/BF00012776. S2CID 6182870.

- ^ Wang, Shaobin; Peng, Yuelian (9 October 2009). "Natural zeolites as effective adsorbents in water & wastewater treatment" (PDF). Chemical Engineering Journal. 156 (1): 11–24. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2009.10.029. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Wastewater resource recovery can fix water insecurity and cut carbon emissions". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ "Is wastewater the new black gold?". Africa Renewal. 10 April 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ UBA (Umweltbundesamt) (2014): Maßnahmen zur Verminderung des Eintrages von Mikroschadstoffen in die Gewässer. Texte 85/2014 (in German)

- ^ a b Walz, A., Götz, K. (2014): Arzneimittelwirkstoffe im Wasserkreislauf. ISOE-Materialien zur Sozialen Ökologie Nr. 36 (in German)

- ^ Borea, Laura; Ensano, Benny Marie B.; Hasan, Shadi Wajih; Balakrishnan, Malini; Belgiorno, Vincenzo; de Luna, Mark Daniel G.; Ballesteros, Florencio C.; Naddeo, Vincenzo (November 2019). "Are pharmaceuticals removal and membrane fouling in electromembrane bioreactor affected by current density?". Science of the Total Environment. 692: 732–740. Bibcode:2019ScTEn.692..732B. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.149. PMID 31539981.

- ^ The publication platform of federal law of Swiss: Verordnung des UVEK zur Überprüfung des Reinigungseffekts von Maßnahmen zur Elimination von organischen Spurenstoffen bei Abwasserreinigungsanlagen, 1. December 2016 (in German)

- ^ EUR-LEX - Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council Concerning Urban Wastewater Treatment (Recast)

- ^ EUR-LEX - Directive (EU) 2024/3019 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2024 concerning urban wastewater treatment (recast) (Text with EEA relevance)

- ^ Margot, J.; et al. (2013). "Bacterial versus fungal laccase: potential for micropollutant degradation". AMB Express. 3 (1): 63. doi:10.1186/2191-0855-3-63. PMC 3819643. PMID 24152339.

- ^ Heyl, Stephanie (13 October 2014). "Crude mushroom solution to degrade micropollutants and increase the performance of biofuel cells". Bioeconomy BW. Stuttgart: Biopro Baden-Württemberg.

- ^ Logan, B.; Regan, J. (2006). "Microbial Fuel Cells—Challenges and Applications". Environmental Science & Technology. 40 (17): 5172–5180. Bibcode:2006EnST...40.5172L. doi:10.1021/es0627592. PMID 16999086.

- ^ Lienert, J.; Bürki, T.; Escher, B.I. (2007). "Reducing micropollutants with source control: Substance flow analysis of 212 pharmaceuticals in faeces and urine". Water Science & Technology. 56 (5): 87–96. Bibcode:2007WSTec..56...87L. doi:10.2166/wst.2007.560. PMID 17881841.

- ^ "National Prescription Drug Take Back Day". Washington, D.C.: U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Henze, M.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Ekama, G.A.; Brdjanovic, D. (2008). Biological Wastewater Treatment: Principles, Modelling and Design. IWA Publishing. doi:10.2166/9781780401867. ISBN 978-1-78040-186-7. S2CID 108595515. (Spanish and Arabic versions are available online for free)

- ^ Von Sperling, M. (2015). "Wastewater Characteristics, Treatment and Disposal". Water Intelligence Online. 6: 9781780402086. doi:10.2166/9781780402086. ISSN 1476-1777.

- ^ "Centrifuge Thickening and Dewatering. Fact sheet". EPA. September 2000. EPA 832-F-00-053.

- ^ "Belt Filter Press. Fact sheet". Biosolids. EPA. September 2000. EPA 832-F-00-057.